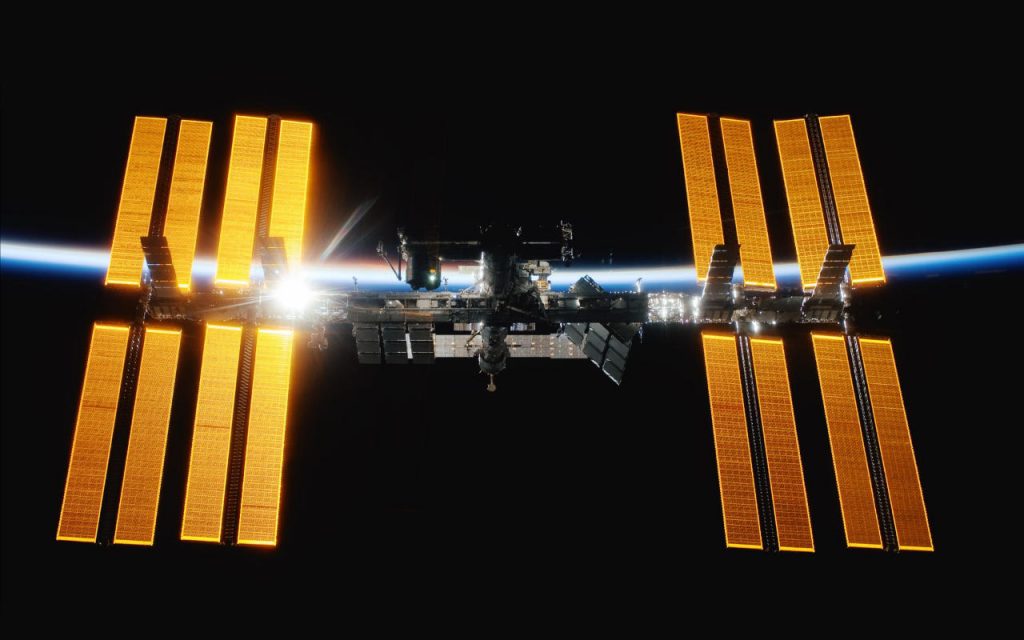

November 2021 marks 23 years of Earth orbits made by the International Space Station. It has been occupied for 21 of those years, by astronauts and scientists from all over the world. Among the most famous residents of the ISS are Mikhail Kornienko and Scott Kelly – who each spent 340 consecutive days on board the ISS. They remain the longest serving residents of the space station, in its entire 23 year history.

But their achievement is practically dwarfed by that of Valeri Polyakov, who spent almost 438 straight days on the Russian space station Mir, between January 1994 and March 1995 – the longest time anybody has ever spent in space.

Spending months on end in space requires huge stores of food, regular food deliveries and a way of keeping all that food fresh for the course of the mission. So, how do astronauts get food in space – and what does polythene packaging have to do with it?

To answer those questions, we need to go right back to the 1960s, where the history of space food begins.

Space food packaging: where it began

The first foods eaten in space were pastes of meat, dispensed from aluminium toothpaste tubes. This developed into freeze dried foods that could be rehydrated in flight, and compacted bite-sized cubes of foodstuffs.

It doesn’t sound very appetising – and it wasn’t. The first astronauts hated the food they had to eat. It was difficult to prepare, tasted bad, and crumbs would often find their way into the spacecraft controls. Worst of all, their launch day breakfasts were designed to reduce their need for the toilet while on a mission (space toilets hadn’t yet been invented), which made them uncomfortable.

That all changed with food science. And of course, food grade polythene.

Read more: Food grade plastics: what you need to know

During the Apollo missions, new space food packaging and preservation methods were developed, to offer astronauts on the week-long round trip to the moon palatable, nutritious, hot meals. Apollo crew members now had a wide range of foods to choose from – freeze-dried soups, casseroles and scrambled eggs, as well as heat-treated and irradiated meat products (briefly exposed to radiation so they wouldn’t grow bacteria).

New “wet packs” allowed food to be rehydrated and warmed up with hot water. And the main material used for space food packaging was polythene.

Why polythene?

Not only is food grade polythene watertight and strong, it’s super compact and light. That’s hugely important, because weight and space allowances on space flights are extremely strict. Even small discrepancies can alter the way a spacecraft flies, so precise measurements must be known beforehand; once you light a rocket, there’s no going back. It’s going in the direction you’ve pointed it, and changes to course are only going to be very minor. You need to know what to expect – including exact weights and measurements of payload, crew and food.

The food weight allowance is limited to 1.7kg per person, per day on the ISS. The packaging weight is considered in that allowance – roughly 450g – so the lighter it can be, the more food will be available. Freeze drying helps reduce weight, but it also uses up precious water – so the aim is to reduce packaging weight and improve preservation, to allow for greater quantities of food. Spaceflight and food scientists are constantly working to improve this.

Special blends of polythene, with unique packaging designs, make it possible to vastly improve the shelf life of space food and reduce weight. All foods going to the International Space Station, with the exception of special fresh items, must have a one-year minimum shelf life – so the food packaging and preservation has to be solid and reliable.

With many space foods, this is achieved by using layers of food grade polythene sheeting; applying protective outer layers, foil layers and inner contact surfaces. The food is placed inside and then vacuum sealed. Further treatment – such as heat-treating or irradiation – can be applied to the vacuum sealed food, keeping weight to a minimum while ensuring maximum freshness.

These techniques have been used on Earth, too. The development of space food packaging has greatly improved the shelf life of all kinds of foods we can buy today, from pre-cooked rice and noodles, to sauces and dairy products.

But getting food into space is very different from the way it arrives at your local supermarket.

Modern space food logistics

The food eaten on the ISS today isn’t all that different from the food we enjoy on Earth. There’s even an espresso machine on board for freshly-brewed coffees – called ISSpresso, of course. To get there, food has to be delivered by rocket. And that in itself is a major challenge.

Food and supply deliveries are made to the ISS every 90 days. Every nation on board has a supply line – and dedicated local menus for their crew.

First, all foods are prepared, treated and sealed about a month in advance, before being delivered and stored at the spaceport. Fresh foods arrive at the very last minute, to keep them as fresh as possible. Food and supplies are then loaded onto an uncrewed, automated delivery vehicle – carefully packed to avoid damage and spoilage during the often violent launch. The cargo is also insulated, to protect it from the extreme temperatures of launch and spaceflight.

Once the automated delivery arrives, the crew uses a robotic arm on the outside of the ISS to catch it, and berth it on a hatch at the side of the station, so it can be accessed. After unpacking their delivery, waste is loaded back into the delivery vehicle, which is then jettisoned. It falls back to Earth, but burns up in the atmosphere long before it reaches the ground.

And that’s it – another 90 days of food shopping done for the crew of the ISS!

Buy Food Grade Polythene Packaging

Do you have any questions about food grade polythene? Call our friendly team on 01773 820415 for advice and help with food grade layflat tubing, polythene packaging for food – or get a quote now.